When a MacGuffin is not a MacGuffin

How students get it wrong, and why story structure sets it right.

Every year, someone brings it up: “Is the Infinity Gauntlet a MacGuffin?” “Is the suitcase in Pulp Fiction a MacGuffin?” “Wait, what is a MacGuffin, again?”

And I get it. It is one of those terms that sounds like it should unlock the secrets of the plot. But most of the time, the conversation veers off into “things characters want” or “important objects,” and the actual function of the MacGuffin, as a narrative device, not a meaningful object, is quietly lost.

So maybe it’s time to say it clearly: a MacGuffin isn’t special because of what it is, but because of what it does. And often, that thing students are pointing to isn’t a MacGuffin at all.

The Hitchcock Problem

For such a simple concept, it is a confusing name. I spend more time silently cursing Hitchcock for giving us the word “MacGuffin” than I’d care to admit, especially in international settings, where the obscure idiosyncrasies of English (as used by the British) are a whole lesson unto themselves.

I usually get a bit short-circuited and end up saying something like: “It’s not a MacGuffin. Forget that label. It’s a plot device.”

But this just confuses the students more.“What do you mean it’s not a MacGuffin?”

And then, well, you can see the mess I’ve landed myself in. “Okay, the suitcase is a MacGuffin... but it is also just a storytelling device.”

This is met with baleful silence. And so I begin the task of explaining why the Infinity Gauntlet is not a MacGuffin, but the suitcase is, while continuing to curse Hitchcock.

So, what is a MacGuffin?

Hitchcock is credited with saying, “The MacGuffin is the thing that the spies are after, but the audience doesn't care.”

A MacGuffin can be:

A physical object (e.g., secret papers, a briefcase, a necklace)

A goal or pursuit (e.g., capturing a spy, reaching a location)

A person (e.g., a kidnapped child, a missing scientist, someone being searched for)

Occasionally, an idea or mystery, but only if it functions as a motivator, not as a theme (e.g., “the formula,” “the truth”)

A MacGuffin is usually a physical object, but it can also be a goal, a person, or a secret. The key is that the characters care deeply, but the audience does not need to.

Two of Hitchcock’s clearest examples:

The stolen money in Psycho

The microfilm in North by Northwest

Neither ends up mattering, and that is the point. For Hitchcock, plot was a delivery system for suspense, not meaning. The MacGuffin motivates the characters, but it is emotionally empty to the audience.

Think about Psycho: once Marion arrives at the Bates Motel, do we even care about the money?

Story is Paramount

Nobody cares about your film if you are not telling them a good story. Enter or exit the MacGuffin, let’s call it a device, as a neat way to get that story moving. It sets up desire. The protagonist (and often the antagonist) wants something.

This fits easily into the classic three-act structure:

Act I – The want is introduced (MacGuffin as inciting incident)

Act II – The want is pursued (conflict, obstacles, stakes)

Act III – The want is fulfilled or denied (the MacGuffin may vanish)

But the MacGuffin is only one possible entry point into plot, because sometimes, the audience does care about what the protagonist is chasing. They care a lot.

To segue students into thinking about story structure more broadly, I might introduce them to two films and ask them to identify what they think the MacGuffin is. Full disclosure: Neither of these films contains a literal MacGuffin. But that is the point, it helps clarify the difference between form and function.

A MacGuffin’s job is to motivate the protagonist, and that is why students often start labelling anything that drives action as a MacGuffin, even when it isn’t.

Rashomon (1950) – Kurosawa

The crime, a rape and a murder, is the central incident that drives the plot. But what matters is not solving the mystery. It is how each character’s version of events reshapes the audience’s perception.

If anything acts like a MacGuffin here, it is the pursuit of truth: it motivates the characters and keeps the audience engaged, yet remains ultimately unreachable.

The incident launches the story, but the real subject is human perception and the instability of memory.

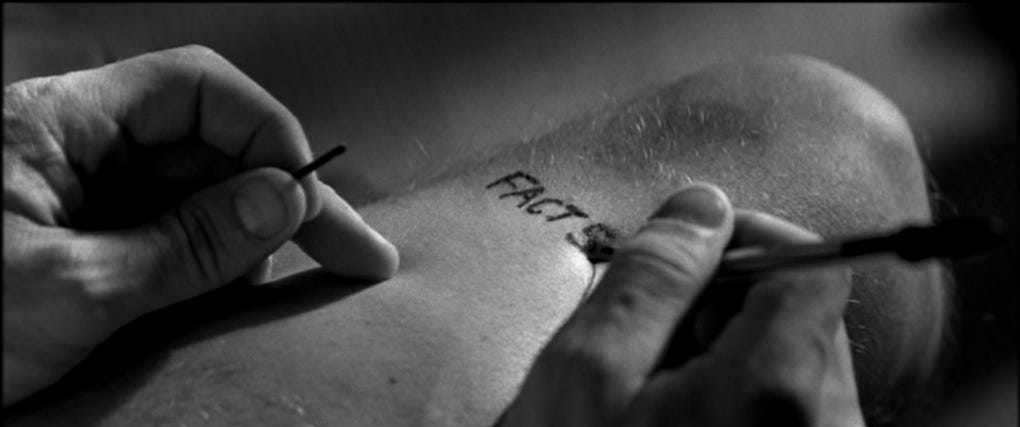

Memento (2000) – Nolan

Leonard’s wife’s murder seems like the MacGuffin, it is what appears to drive the plot. But as the film unspools (in reverse), we realize the true mechanism isn’t the murder. It is Leonard’s memory.

Memory here is both structure and device - the engine of the story and the thing most in doubt.

So, can memory be a MacGuffin? Maybe. But in Memento, the pursuit of truth gains complexity and weight. It does not vanish, it intensifies. This is where nonlinear storytelling complicates the concept of a MacGuffin. It is no longer just a “thing” the character chases, but a deeper inquiry into time, identity, and perception.

So if it is not a MacGuffin... what is it?

Usually, it is a plot device, a tool that moves the story forward. Here are some of the key types:

Inciting incident – the moment that changes everything

Character desire – what the protagonist wants (vs. what they need)

Conflict – internal or external barriers to the goal

Narrative engine – the dramatic question or tension that keeps us watching

A MacGuffin is just one form of these devices.

Bringing this into the classroom

The aim here isn’t to test knowledge of film terms, it is to help students think about how story works, what drives it forward, and how plot devices (MacGuffin or not) can shape character and structure.

Here are two possible approaches:

1 - Deconstructing Story

Prompt: Think about the last film you watched. Now break it into a simple three-act structure:

Act I: What starts the story? (Is there an object, goal, or incident that kicks things off?)

Act II: What’s being chased or pursued? (What do the characters want—and who or what is in the way?)

Act III: What’s left by the end? (Does the original goal still matter, or has it changed?)

Discussion questions

Was there a clear plot device driving the story forward?

Did that device stay important, or did the story evolve beyond it?

Would you call it a MacGuffin? Why or why not?

2 - Building Story from a Device

Prompt: Use one of the following to spark a short story idea:

A disappearing object

An impossible event

A false desire (what the character thinks they want, but actually, they don’t)

Have students sketch out a brief outline or beat sheet:

Who is the protagonist?

What do they want, and what drives them forward?

How does the story change if the device is taken away?

Follow-up questions:

What role does your device play in the story? Is it meaningful? Mechanical? A distraction?

Is it something the audience cares about, or just the characters?

And then, just as class is wrapping up, someone looks up and says,

“So… is a MacGuffin also a red herring?”

Great post! Big Hitchcock fan, but I can see what you mean about students getting hung up on the term and divorcing it from the actual meaning. Sometimes when there is a catchy word or phrase for something it's like an invitation to not think about it anymore. In the animation community people LOVE to say "story is king" but don't always act like it