You want to use what? Why? Better yet, how?

As a film teacher to teenagers, I frequently encounter students eager to incorporate non-original materials—like favorite songs or popular commercials—into their projects. However, these additions often lack depth, serving more as aesthetic choices than narrative tools. Young filmmakers must learn that non-original materials can enhance their storytelling in complex, meaningful ways. Introducing them to avant-garde filmmaking approaches can be a great way to encourage a deeper understanding of how referencing in film can transcend mere aesthetics and become a tool for nuanced storytelling and artistic expression

But First - The Misnomer around "Found Footage"

The term "found footage" is widely recognized, particularly in films like The Blair Witch Project (1999), where it serves as a storytelling device; the footage, specifically created for the film rather than pre-existing, fosters the illusion within the film’s world, crafting an immersive, first-person narrative.

In the avant-garde cinema sphere, "found footage" takes on a literal meaning—it is about filmmakers discovering and repurposing existing film clips to craft new narratives or documentaries. This approach offers a fascinating exploration into the re-interpretation of existing narratives to construct new truths.

Some great examples of found footage to explore

Outer Space (1999) by Peter Tscherkassky and Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat (2024) by Johan Grimonprez.

Peter Tscherkassky (Austria) uses found footage to craft visually arresting narratives that challenge conventional filmmaking norms.

Note - if showing Outer Space in a classroom be warned that there are audio and visual triggers for some students.

Johan Grimonprez’s (Belgium) works leverage archival footage to re-contextualize historical narratives, offering fresh perspectives.

Observation - both these artists can be found on the internet in general, and have nicely curated websites.

Bringing this into the classroom:

For educational purposes, it's essential to differentiate between various types of non-original footage:

Found Footage: Often crafted to appear as if discovered, this footage adds realism and immersion to genres like horror and thriller.

Archival Footage: Genuine historical footage from sources such as news outlets or government archives. This footage adds authenticity and historical depth to films, especially documentaries.

Creative Commons Footage: Licensed under Creative Commons, this footage can be freely used under certain conditions, helping filmmakers avoid the costs associated with traditional footage licensing.

Challenge: Creative Use of Non-Original Material

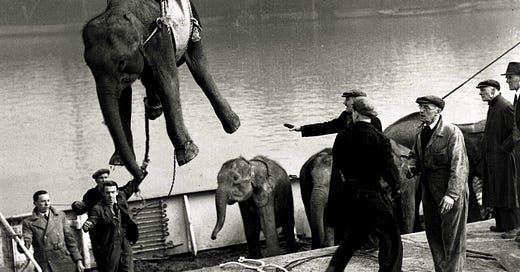

Challenge the students to create short films (30-90 seconds) that incorporate non-original visual or sonic materials. This task is not just about filling gaps but about centralizing these elements within the narrative. For instance, using an image of an elephant being hoisted onto or off of a ship can symbolize various themes—memory, dreams, metaphor, truth, or deception.

Steps for Implementation:

Introduction to Found Footage: Discuss the concept and its relevance in contemporary cinema.

Viewing Examples: Analyze clips that effectively use found footage.

Sourcing Material: Guide students on where and how to find suitable footage.

Ethical Use: Emphasize responsible and ethical use of found footage. This is especially true of footage depicting historical events and real people.

Citation Practices: Teach students how to properly cite non-original materials in their projects.

So, here is my prompt

borrowed from Johan Grimonprez’s Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat (2024).

Invite the students to create a short 30-90-second film that must include this image (or similar footage of an elephant being hoisted onto or off of a ship) to depict one of the following ideas in a larger narrative of their making:

A memory

A dream

A metaphor

A deceit

A truth

The film that they are invited to make must incorporate this image or footage similar to it. The character(s) in their film must have some reason to encounter, think about, or imagine this elephant. This moment is an explanation for something else going on in their imagined film.

That’s it. Take it and run with it.

By understanding and utilizing non-original materials thoughtfully, students can enhance their narrative storytelling, creating films that are not only technically sound but also rich in meaning and creativity.