Listening to The Zone of Interest (2023)

We learn so much about ourselves when we watch film, it serves as a unique space where we can recalibrate our moral compass and engage with scenarios that, while often distanced from our reality, serve to reframe our humanity.

Sound in Cinema

Despite its crucial role, sound in film is often only superficially understood by students. They recognize its presence but struggle to articulate how sound design influences a film's narrative beyond the obvious—explosions, shouts, and music. An understanding and skillful manipulation of sound can profoundly elevate a film. This is particularly evident in the meticulous sound design crafted by Johnnie Burn and Jonathan Glazer for The Zone of Interest. Their nearly two-year process of editing the film, built on a foundation of lifelong expertise, represents one of cinema’s most remarkable achievements: creating a sonic document of a specific time and place.

The film's dual structure - referred to by the team as Film 1 and Film 2 - illustrates this beautifully. Film 1 shows us the visible world of the characters; their home, their mundane realities. Film 2, while never visually presented, encapsulates Auschwitz. It is always there, perceptible only through sound. This background soundscape becomes familiar over time, yet its impact is profound when listened to independently of the visual elements. By reducing visual stimuli and focusing on sound, viewers cross a sensory threshold into the camp itself, breaking down the barriers that keep the horror at a safe, observational distance.

Cultural Context and Sound

This approach enriches film analysis and deepens students' understanding of cultural context. How do you create a soundscape for a real moment in time that is fictionalised? What information do you need to re-create an accurate portrayal of the past? Burn’s method of gathering contemporary sounds that echo historical realities, for instance, capturing the voices of modern-day protestors to stand in for voices from the past provides a tangible link to history.

Bringing this into the classroom:

Introduce students to key sound concepts: ambient, Foley, dialogue, direct and reflected sound, diegetic, and non-diegetic.

Watch Thomas Flight’s Why The Zone of Interest Does Not Let You See to establish context and understanding.

Engage students in exercises where they listen to scenes without visuals to identify and discuss sound elements. This approach fosters active listening and a deeper engagement with how sound shapes a film’s narrative.

Some Guiding Questions

How can sound define time and place?

In what ways is sound a cultural artifact?

What unexpected emotions or reactions did you experience while listening?

How might this experience alter your perception of sound in films?

*Subscribe to Thomas Flight’s work - ask your schools to support a subscription.

After watching Flights' interview with Burn, here are two approaches to explore some of the elements that Johnnie Burn (JB) shared about his process.

Listen to a scene

This classroom exercise is a good way to introduce the expectations around active listening. Decide whether to conduct the exercise as a group in the classroom or allow students to complete it individually using headphones.

Prepare for Listening

In a group, and if possible dim the visuals.

Individually, advise students to minimise visual distractions.

Active Listening

Encourage students to focus solely on the auditory elements of the film.

Ask them to write down the different sounds they identify during the excerpt.

Discussion and Analysis

Have students share the sounds they identified.

Discuss these elements, exploring how each contributes to the overall atmosphere and narrative of the film.

Reflection

Prompt students to reflect on how this exercise changed their perception of the film's sound design and its impact on the storytelling process.

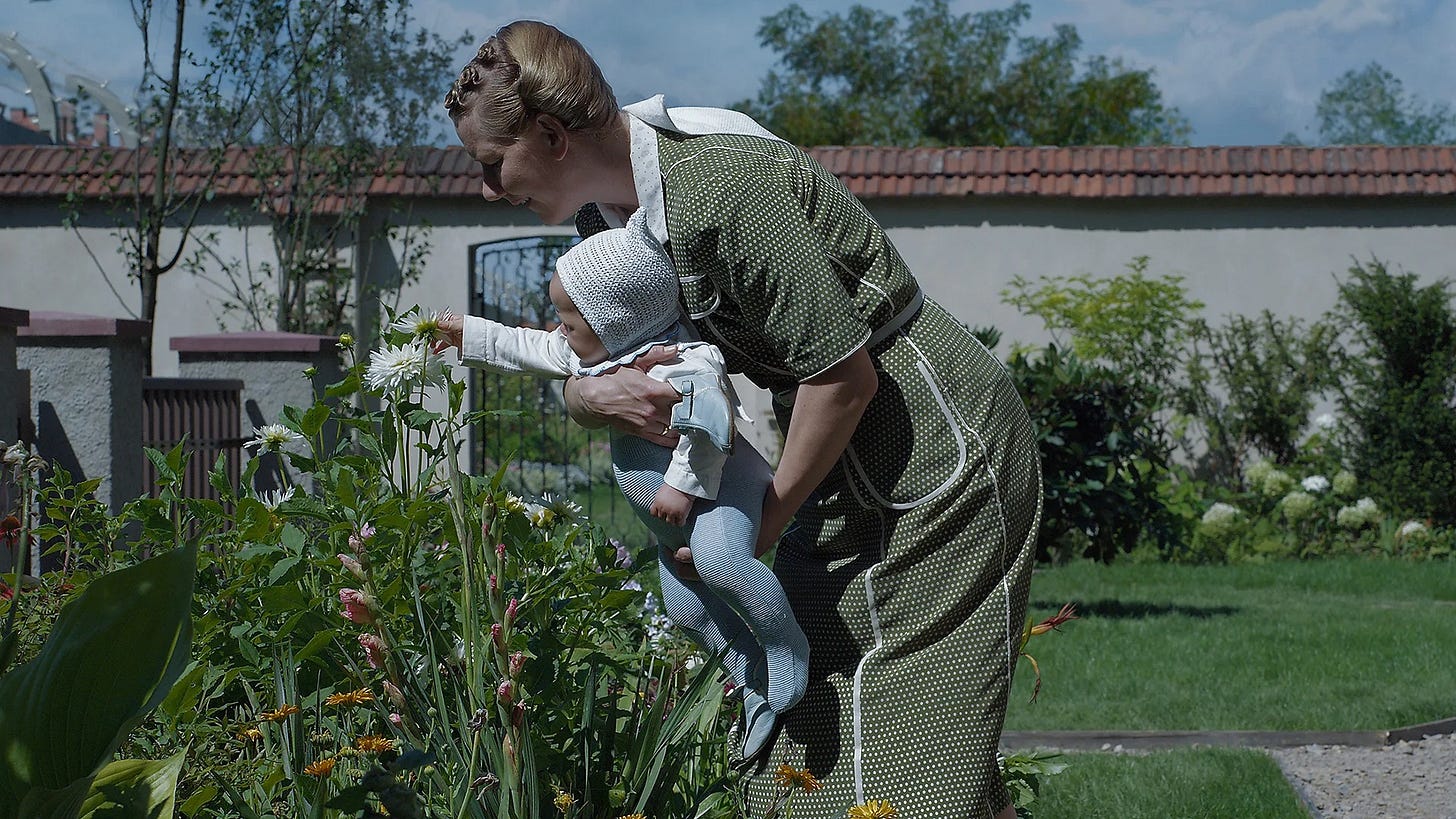

Decode a still

A strong classroom assignment this exercise is also a great take-home assignment.

Select a film still to share with the students or encourage them to choose one themselves. Print it out on paper or project it on a whiteboard (if using one shared image).

Initial Observation

Have students examine the still image and consider the potential sounds they might hear at this moment in the film.

Discuss the concept of Film 1 and Film 2, explaining that Film 1 includes visible elements and Film 2 encompasses elements implied through sound.

Identify Sound Sources

Instruct students to label where they believe sounds from Film 1 (visible elements) and Film 2 (implied elements) are positioned in the still.

Ask them to use directional terms such as: front of frame, back of frame, left of frame, right of frame, top of frame, and bottom of frame, to specify the origins of these sounds.

Sound Annotation

Ask students to annotate the still image with notes about what sounds they hear from different parts of the image.

Have them describe the acoustic properties of these sounds—such as loudness, pitch, and tone - and how the sounds might travel within the scene.

Reflection on Sound

Discuss how different sounds move the viewer’s attention across the film’s geography, impacting the storytelling experience.

Explore how different interpretations can lead to varied emotional reactions and understandings of the film.

Some Sound-related vocabulary

Ambient - Background noises within a scene.

Foley - Special effect sounds added post-production to enhance auditory realism.

Dialogue - Spoken words by characters.

Direct Sound - Sounds captured simultaneously with the image.

Reflected Sound - Sounds that reach the listener after reflecting off surfaces.

Diegetic - Sounds originating from the film’s world.

Non-Diegetic - Sounds added for the audience, not heard by characters.