How did we get here?

This is a question I find myself asking my students quite often when watching their films. A moment of transition, and I turn to them, asking, how did we get here? It's a quick indication that I’m no longer buying into their film world because the geography feels off.

I love a map. As a kid who moved frequently, orienting myself in time and space became a practiced skill. I know this is one reason I can immerse myself quickly in the film world—but it's also why I can be pulled out just as fast. If I can map it, we're good. If not, I’m left trying to figure out how we got here and why it doesn’t make sense.

A film notorious for its creative geography is Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). I’m not going to debate the logic of it—perhaps the layout of the Overlook Hotel and grounds is purposefully confusing. But if you have the time, a fun exercise is to try mapping the geography of the film.

What is creative geography?

Creative geography is an important part of world-building in film. A simple explanation for students is that it’s a technique where multiple locations are combined through editing to give the illusion they are part of the same space or sequence. For instance, a scene may show a character entering a building filmed in one location, while the interior shots are filmed elsewhere. Through careful editing and matching of visual elements like lighting and angles, the audience perceives these locations as a continuous space.

Creative Geography and the Kuleshov

Every film student is introduced to the Kuleshov effect at some point. It’s a simple technique, but beautifully complex in how it creates meaning. Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov (1899-1970) demonstrated that the meaning of a shot is influenced by its context—specifically, the shots before and after it. In other words, viewers derive meaning and make connections between unrelated images simply through their juxtaposition in a sequence.

The connection

The Kuleshov effect shows that viewers will mentally link two images shown in succession, even if they are unrelated, to create a coherent narrative. For example, in Kuleshov’s famous experiment, a neutral expression on an actor’s face was shown after different images (a bowl of soup, a reclining woman, a child in a coffin), and audiences interpreted the actor’s emotion based on the context of the second shot, whether hunger, desire, or sadness, despite the expression staying the same.

In creative geography, the viewer perceives separate, physically unconnected locations as a unified, continuous space due to the way they are edited together. Filmmakers manipulate spatial relationships by cutting between shots of different locations or sets, convincing the audience that they are looking at a single, seamless environment.

Both concepts rely on the audience’s ability to infer meaning from the sequence of shots. With the Kuleshov effect, it’s emotional or intellectual meaning. In creative geography, it’s spatial continuity. In both, the audience fills in the gaps, creating coherence where it doesn’t naturally exist.

Types of creative geography (not an exhaustive list)

Linking geographically distant locations

Combining shots from far-apart places to create the illusion of a single continuous space. (City of God, 2002)Blending the real and unreal

Tying real locations with CGI, constructed sets, or visual effects to merge reality with fantasy. (Inception, 2010; Pan’s Labyrinth, 2006)Using one location to represent another

Filming in one city or location that stands in for another. (Good Will Hunting, 1997)Nonlinear geography

Disjointed or fragmented continuity where different locations are pieced together in ways that don’t follow logical geography. (Run Lola Run, 1998)Combining miniatures with live-action footage

Blending scale models or miniatures with real footage to create expansive environments. (Star Wars series)

Bringing this into the classroom

Key concepts:

Creative geography as a technique for world-building in film.

Montage and the Kuleshov effect, emphasizing psychological editing and how the audience actively participates in making meaning from a film.

Being able to identify the need for creative geography in one’s own work.

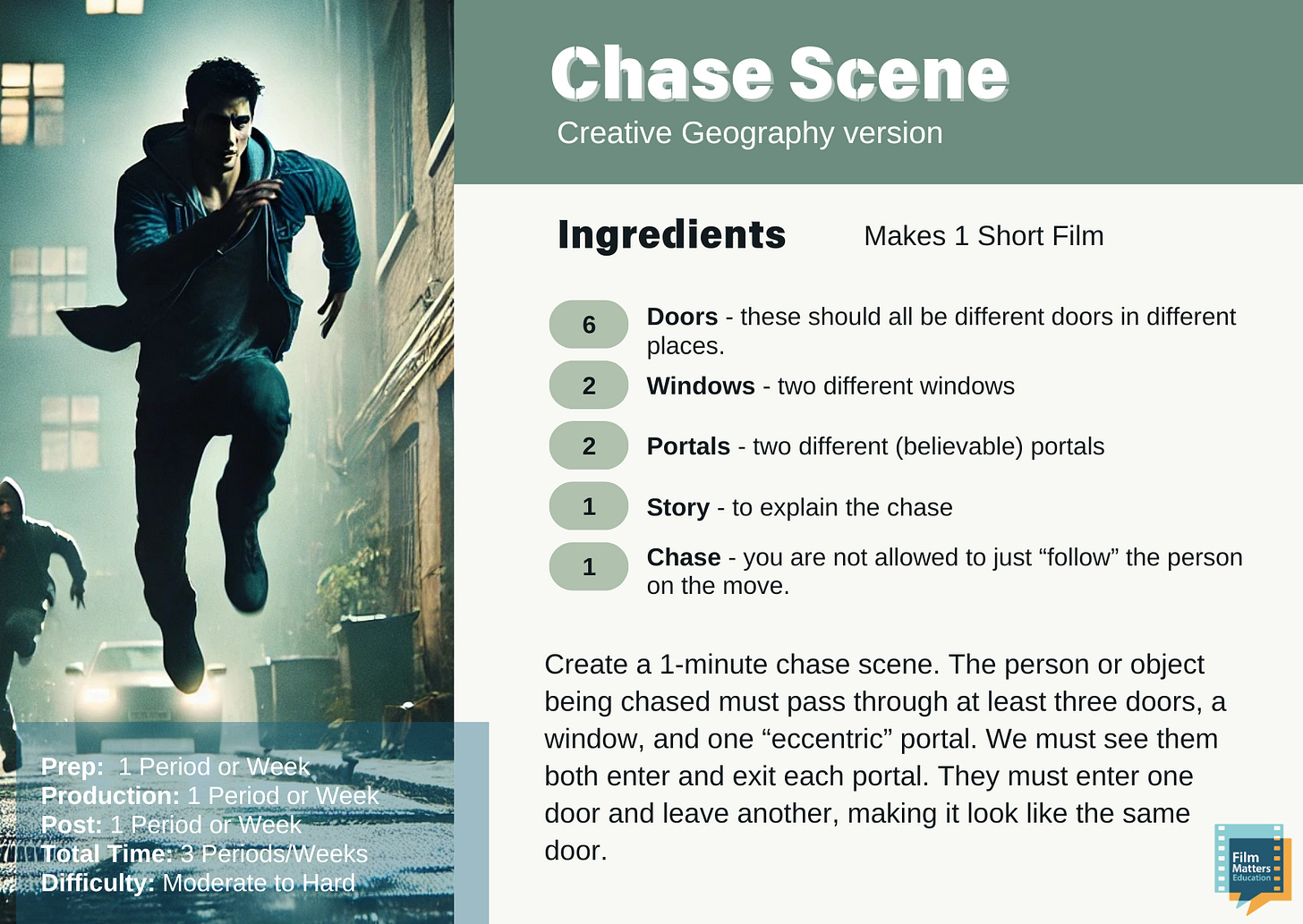

Challenge: Chase scene (A classic film exercise)

Create a 1-minute chase scene. The person or object being chased must pass through at least three doors, a window, and one “eccentric” portal. We must see them both enter and exit each portal. They must enter one door and leave another, making it look like the same door. This doubles the number of portals. Here’s how the transitions break down:

So, to be clear: the location of Door 2 is different from Door 1, and it’s indeed a different door. The transitions don’t need to happen in this order; they just need to occur at some point in the film.

What needs to be done:

Come up with a story. The chase needs to be grounded in a narrative, and the actors need to understand why the chase is happening and who they are as characters.

Plan your film world, build the chase.

Storyboard the chase (create a map).

Think about how shots will fit together. Ask yourself how the sequence will cut together and whether your audience will buy into your film world.

Plan your sound. The aural texture is an essential component of creative geography.

Be smart and stay on the ground! Have fun.

The Safety Talk

Many of us are working with teenagers, so it's crucial to have a safety talk about the doors, windows, and portals in this exercise. Teenagers aren't always risk-averse, so be sure to set clear ground rules. Remind students to stay on the ground and exercise caution - no climbing through windows or doors without ensuring everything is safe and secure. The nature of the challenge needs to be understood: stay on the ground, avoid risky stunts, and use extreme caution.

Safety first, always!

You might also like: